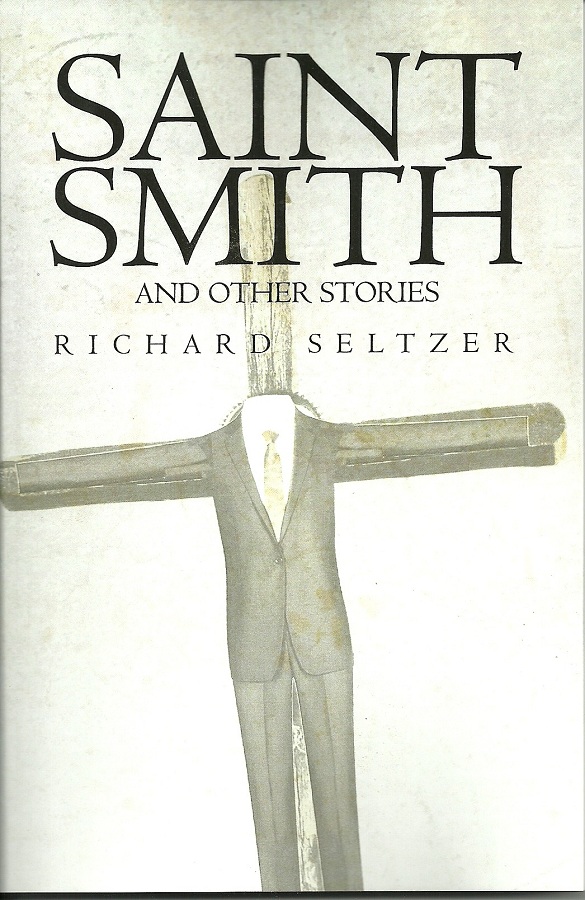

Saint Smith and Other Stories by Richard Seltzer

Chapter One -- Contagious Dreams

Chapter Two -- Mansions and Castles

Chapter Three -- Aunt Rachel and the Wizard of Oz

Chapter Four -- Charlie's Coming of Age

Chapter Six -- The Pictures from Charlie's Wedding

Chapter Seven -- Irene in Munich

Chapter Nine -- The Light House

The

Choice, 2009

The Gentle Inquisitor, 1977

Creation Story, 1970

Chiang Ti Tales, 1970

The Mirror, 1991

The Barracks, A Novella, 1989, 1990

Saint Smith

Chapter One -- Contagious Dreams

July 1966, Silver Spring, Maryland

The rest of the family was gathered in the living room playing instruments or singing songs, for the grandparents' sixtieth anniversary. Frank escaped upstairs, unnoticed in the dense crowd of relatives. He heard a noise nearby and found Irene, his uncle Charlie's wife, stretched out on her back on the bed in the guest room. With her dress awry, the upper part of one thigh was exposed. Frank stopped and stared. Then she sat up, looked at him, and smiled.

"Was denkst du?" she asked. She sometimes let him practice German with her, for the beginner's course he was taking in college. When he didn't answer right away, she asked again in English, "What are you thinking?"

Frank asked, rather than answered, "How did you get your name? Irene isn't a German name, is it?"

"That name I chose," she said. "Helga my parents called me. Ich heisse Helga, Helga Heinz."

"Then Helga's your real name," he concluded.

"No, my real name is Irene. Helga they called me."

"And what does Irene mean?"

"Peace. And before Irene, Iris my name was."

"Iris?"

"The rainbow -- messenger of the gods. A bold name, nicht wahr?"

"Why change your name twice? Were you trying to hide something?" I asked.

"When you change, your name should change. Your name should harmony with you have."

"What?"

"The presence of God have you felt?" she asked, gesturing for him to sit beside her on the bed.

From downstairs, the volume of the music increased as the family reached the refrain of "A Mighty Fortress Is Our God."

The guest room was filled with conflicting shadows from the light in the hall and from the moon outside the window. There were two single beds in the room. Frank's father and his Uncle Fred had slept there as boys. Later, the room had been his uncle Charlie's. Pennants from the University of Maryland, where Charlie had been accepted and planned to go, still adorned the walls.

Charlie's high school wrestling trophies still filled a bookcase in the corner. Granny had interspersed glass elephants and giraffes among the trophies and on the bureaus and windowsills. She had hung a brass crucifix between the windows. Over one bed, the one that had been Charlie's and that Irene and Frank were on now, hung a framed reproduction of a painting with a determined-looking young man, very much like Charlie, holding the steering wheel of a ship and looking up and ahead, while Christ stood behind him with a hand on his shoulder.

"This crazy woman, you think. Religious nut, nicht wahr? But me back in Heidelburg, that you should see. Iris -- the messenger -- I was. Now Irene -- peace -- my name is."

She put her hand on his shoulder.

Frank looked up at the painting of Christ and the ship's pilot and felt a twinge of guilt. Irene was the most sensuous woman he had ever met. He was hoping for the miracle of a caress. Instead, she spoke of God.

"Have you ever God beside you felt? God Himself, living and breathing?"

He stared at her, lost in her deep blue eyes.

"Imagine that Christ returned, and you his return made happen," she said. "Or imagine each of us Christ is. A spark within us from God comes. And, sometimes, that spark can flare and brightly burn.

"I'm silly think you. Sehr gut. Perhaps my words no truth hold. What could this crazy lady know?

"I will you a story tell. The story of Der Heilige Schmidt. Heinrich Schmidt his parents him called. Heilige Schmidt we came to call him. Hank Smith, Saint Smith would you call him.

"All Sturm und Drang, all struggle and push, was I, like Charlie now. I would my mark on the world make. Very proud was I of my cleverness.

"I drama and literature studied, at Heidelberg. One day I great literature would write. Already, to me the world a stage was. My living, what I did and what I said would a masterpiece make."

"Performance art?" Frank suggested.

"What you say -- yes. Only not so big a deal. At the beer keller, my friends and I tales and jokes made -- not just with words, with what we did."

"Practical jokes?".

"Yes, that we did. Heinrich sometimes with us joked, but shy he was, quiet. We mocked; we laughed; we tricked."

"He was the butt of your jokes?"

"Yes, perfect was he as victim -- everything he believed.

"He was gullible."

"'Ghost bags' we made."

"What are those?" Frank asked.

"Hot-air balloons, yourself you make. You this for fun at college do, nicht wahr?"

"No," he admitted.

"Ach! This must you learn. First, a cross with two pieces of wire you make. Little candles, birthday candles where the wires cross you melt. Plastic bag for clothes you take."

"Dry cleaners' bag?"

"Yes, and bag to wires you tape, with bag wide open."

"Okay. So why bother? What can you do with it?"

"At night, on roof you go, tall roof. The candles you light, the bag you hold. The bag with hot air fills. Let go. Let fly. For miles will it go. Bag with smoke filled, light bright and ghostlike shines.

"This we did, from the roof of Heinrich's building. Ten bags, one after the other. One of us with him in his room was. Heinrich the ghost bags saw -- lights through the city flying. Heinrich through the halls ran, 'Fliegende geiste!' he shouted."

"You mean flying saucers?"

"Yes. A week he classes missed."

"Okay. I get it. He was embarrassed. He couldn't show his face."

"As you say. Then telephone, we the telephone trick did."

"What trick?:

"You lessons on pranks need? So simple -- telephone and ball point pen. Telephone a dial has, and a receiver. When down the receiver goes, down the buttons go; and the call ends. Pen a metal clip has, for pocket. And clip round part has, like ring. From two pens the ring take. Rings on buttons put, so receiver rests; buttons don't down go; call ends not.

"Like this, I Heinrich's phone fixed. Receiver down but phone on. I with the dial played -- like fooling. I my own number dialed. When to my room I went phone still rang. When I receiver picked up, everything from Heinrich's room I heard.

"Like a bug?"

"Yes, homemade bug. No cost, just fun. Friends in my room listened. Heinrich in his room lines from play practiced. We at him laughed. He laughs heard, but where the noise came from, he knew not. He shouted. We louder laughed. He here and there ran, everywhere looked -- where this sound? We louder laughed.

"He must have been freaking out."

"Freaking, yes. That word. Very scared.

Ran very fast, very far. Room geistlich."

"Haunted."

"Yes. Good laugh."

"Okay. So you pulled some practical jokes on him. What's the big deal? "

"The big deal next came. A play I wrote -- 'All God's Children.' Satan God tells, 'Why to Earth you go? Why to Earth you your Son send? Why with man games play? All people your children are, nicht wahr? One man, any man, wake up. To one man truth make known -- the truth that he God is.'

"In my play, God said, 'Sehr gut. Miracles from inside make, not outside. Miracles not from God; from man by the free will of man. I will one awaken, one to be to all the rest a guide. One of my children among them god-like to be.'

"In my play, God a carpenter chose. And to waken him, no angels, no burning bush came. His brothers and friends a joke played.

"Imagine Jesus at age twelve. To his parents, obedient and trustworthy was he -- a fine young man. He with his father worked; he with his mother helped. To his brothers proud and pompous was he. 'Little God' they him called.

"One night, when he slept, his brother James near his face a torch waved, then ran. Outside the window, others shouted, 'I am the Light!' He did not wake. Nothing. The next night, again they tried, again he slept. And a third night, and again he slept.

"Then the morning after the third try, Jesus a new person appeared -- selfless, humble, kind. To everyone he listened, for everyone he cared. His look and his words everyone comforted and inspired. 'A light unto the world' he became.

"Proud was I of this idea. But my friends mocked. Real people like this do not act. To prove my point, I myself tried. There and then, a modern version of that same joke, with Heinrich as victim I played.

"A tape recorder and camera flash I near his bed placed, with timer. In the middle of the night, the bulb would flash and the recorder would boom, "I am the light!"

"What would he think? How would he act? At least down the hall would he run and scream. More flying saucers, more laughs for us. Wild tales would he tell.

"But nothing. He just slept. So again I tried, and yet again, as in the play. Still nothing. . I stopped. Mein Gott, was I foolish.

"Then a week later, Heinrich changed. He with warmth, concern, and tenderness glowed. His deep blue eyes they compelled. His voice, his words they resounded. Even strangers everywhere him followed. With these followers, he the streets roamed, night and day. Good will and joy he spread. The poor and homeless help he gave. No preaching, just doing. Such confidence. Such strength of will.

"Me and my friends -- we who had nothing believed -- we, too, his followers became. Der Heilige Heinrich, Der Heilige Schmidt, Saint Smith we called him. And my friends named me 'Iris', crediting me, my play, my joke for this miracle. A 'messenger of the gods' was I for this new cult.

"Only Heinrich didn't know. No one about my trick had told him. No idea had he a joke this change had made. I what I had done must confess.

"In public him I told, so friends and followers would hear. Before him I knelt like to a God, and begged forgiveness.

"His eyes blank and cold became. Who was this? Not Der Heilige Schmidt and not the old Heinrich. I screamed. Him I grabbed. Him I hugged. Him I shook. Gone. The magic, the godliness gone.

"Then knew I that I had loved him. As God-in-man I had loved him. That heilige man had I loved.

"The cult ended. The followers they blamed me. 'Fraulein Judas' they me called.

"With him I stayed. With my body I him loved. No soul. No magic. Flesh rubbed flesh.

"I became pregnant. I an abortion had. I Heinrich left. I the university left. Irene I called myself. Peace I needed."

As she paused -- Frank became aware of the music from downstairs, the chorus of "Gloria In Excelsis Deo." His muscles were stiff. He hadn't moved during her narration. His right leg had gone asleep, but he didn't dare shake it. He didn't want to disturb her concentration. He wanted her to continue.

"You at my eyes stare," she noted, "not in them, but at them. Yes. They are blue, like Heinrich's, but not heilige. When he God was, when god-in-him was, his eyes you out of yourself drew. I this story poorly tell; even in German poorly. Forgive my awkward words. If once you see, no need for words. If not, words nothing do.

"Sometimes Charlie that look has. When I him in Munich first met, he that look had. He, a GI with a camera, on a street in Munich stopped me. In broken German said he, my 'face' he needed, as a model. He would me pay. Well knew I that not my face he wanted. He me followed, pictures taking. At the corner, I stopped, turned, and smiled. 'Okay,' said I in English, 'let's about your pictures talk.'

"We to a beer keller went. The story of Der Heilige Schmidt I him told, not like a story I had lived, but like a story I had written. His eyes then, they looked deep like Heinrich's. On and on we talked about the Saint Smith story, about making a movie based on that. A masterpiece it could be, said he. First must he master his craft. .

"At our wedding, too, his eyes that deep look had. And sometimes too, his eyes even now that way flash even, when me he wants and only me."

"Frankie!" his mother bellowed from downstairs. With a start, Frank reawakened to the world in which his parents treated him as if he were still a little kid. He hated being called Frankie. "Frankie!" she bellowed again.

"Yes, Mom?" he called back automatically.

"Get down here this instant. Are you deaf? It's time to go home."

With his right leg still painfully asleep, he stumbled and hobbled to the door. Irene didn't notice. She kept looking in the same direction and with the same expression. He didn't want to disturb her, and besides, he had to hurry. But he wondered if she continued to talk, even after he left.

Chapter Two -- Mansions and Castles

August 1940, Silver Spring, Maryland

"Sarah, you did write the boys, didn't you?"

"Yes, Hank. Of course." Sarah poured him a cup of coffee. The kitchen seemed larger than before. She had to stretch to reach the breakfast dishes in the cabinet and to put them in their proper places at the table. "You know I write every day."

Hank gulped his coffee. "Wyoming isn't on the other side of the world. How long could it take for a letter to get there? They should have started home when Sue first turned sick." His voice dropped. "Now she's been dead a week... Where in God's creation are they?"

Sarah stopped. She didn't need to put a plate at Sue's place. "Yes. Of course. In God's creation."

Hank looked up at his wife in surprise -- a delayed reaction to the bitter taste of unsweetened coffee. At that moment he realized her voice had changed. It was like the voice of some older relative of hers -- familiar, but strange.

He looked at her more closely as she returned the extra plate to the cabinet, then adjusted her own plate, fork and spoon. A few streaks of gray in her black hair framed her face and gave it definition. If nature hadn't provided those streaks, a hairstylist might have. Hers wasn't the fragile beauty of youth that changed with a shift of mood, or the beauty of middle age that changed with fashions. She knew who she was and was pleased with her life. But today her self-confidence was shaken. Her mouth was set in a thin expressionless line, and her eyes, which seemed darker than before, avoided contact with his. She had changed, and he had, too. This last month had been hell for them both. "Sarah," he said gently, "I was talking about Sue."

"Yes, Hank. Sue. Where in God's creation? And where's the sugar?" She stood up. "Nothing seems to be where it should be." She groped among the canisters and jars of preserves on the counter.

"It seems you spend your whole life straightening and cleaning," he said. "The house is getting too big to handle."

She turned and looked him straight in the eye. "How does a house grow, Hank?"

"If houses really grew, I'd be out of business."

"In John 14 it says, 'In my father's house there are many mansions.'"

"I thought the word was 'rooms.'"

"'Rooms' in the Standard Revised. 'Mansions' in the King James. I always wondered how a house could have mansions, instead of rooms. But that's how this place feels to me now -- the rooms seem huge."

"If a customer told me that, I'd take it as a compliment, but from you..."

"I love this house. You know that. There's nothing like it in the world. I could sit for days curled with a book on that bench in the alcove by the fireplace."

Hank slowly stroked his mustache. "Maybe it's time to think of building another smaller place that would be easier to care for," he suggested. "After all, Russ will be leaving for college next month, and then Fred. Then there will be just the two of us in this big old place. It's time to move on."

"Don't talk of moving," she said quietly, but firmly.

They heard footsteps on the walkway, and both grew tense with expectation. At this time of the morning, it could be either Rem Jones the mailman or the Reverend Schumacher. If it was Rem, there could be another letter from their sons.

Their ten-year-old daughter, Sue, had died suddenly of pneumonia while her two teenage brothers were away camping on their Uncle Harry's ranch in Wyoming. The boys wrote home often, with messages intended for Sue.

There was no telephone at Uncle Harry's ranch, so Hank and Sarah couldn't call and tell them that Sue had died. And Sarah had insisted that a telegram would be too cold and cruel. She had written them a letter, but couldn't bring herself to mail it, though she let Hank believe she had sent one letter after another. Instead, she added to the first, unsent letter each day, and her guilt at not sending it grew as Hank became more and more impatient with the boys for not coming home.

Two days ago, Hank, who was normally cool-headed and practical, threw a screaming fit when another letter from the boys arrived. The unintended irony of their references to Sue pained him, and he lashed out at them.

Sarah found some consolation in that same letter. As long as the boys didn't know, to them Sue was still alive.

The footsteps on the walkway had the light, quick pace of the young Reverend Schumacher.

Hank took a deep breath and sipped his bitter coffee. "Why did I ever let them take the car?" he asked rhetorically.

"It's the only way to get there. You said so yourself. The train would leave them a hundred miles from the ranch, and besides, we simply couldn't afford it."

"Then they simply shouldn't have gone."

"It was time they grew up and learned to go off on their own and rough it. That's what you said."

"And what's the point of their seeing Harry? I know he's your last living uncle, and we can't expect him to live forever. But he'll just fill their heads with war stories -- as if they don't get enough of that from the books he sends them every Christmas and birthday, and now the newspapers are full of that new war in Europe. To hear Harry talk, you'd think that war was the greatest thing that ever happened to a man -- a chance to see the world and be a man among men. The less we hear from him the better."

At the outbreak of World War I, Harry, at the age of 39, had left behind his wife and children and volunteered to join the American Expeditionary Force under General Pershing. He had received a field commission and, by the end of the war, rose to the rank of captain. After the war, he traveled for two years in Russia, the Middle East and North Africa, purportedly on military-diplomatic missions. He loved to talk about those times and exotic places and to show off the coins, postcards, photos, and artifacts he had collected. But to any question about what he did there, he replied with a wink, "I'm not at liberty to divulge that."

Now, at age 62, Harry lived with his second wife, Martha, age 33, and their three-year-old daughter Matilda, on a large ranch in Wyoming. He named the ranch "Cairo," and in addition to cattle, he raised camels, which he sometimes sold to circuses and zoos, but mostly kept for his own amusement -- holding endurance races across the barren plains.

"Harry's harmless," said Sarah.

"Harmless? The man's a dream-maker, and there's nothing in this world more dangerous than that. If it hadn't been for my grandfather and his sand castles, I'd have never ended up a builder."

"And do you regret it?"

"No, but that's not my point."

_____________________________

The Reverend Schumacher, a Lutheran minister, was 25 and unmarried. At first, Sarah had found it difficult to turn for solace to a minister half her age, who had hardly known Sue. But he was so sincere and ardent, she couldn't turn him away. Since the funeral, the Reverend came by nearly every morning to sit with her in Sue's old room, often in silence, but sometimes reading passages from the Bible and then talking about them.

Sarah admired his erudition, his familiarity with foreign languages, and his faith that the words of the Bible are the words of God Himself. It was refreshing to see a young man who felt he had an important mission in life. She hoped he would be able to keep that faith for many years.

Russ was planning to go into the ministry. He'd be starting at Gettysburg College next month, in pre-seminary. Sarah wondered if Russ would ever be this ardent and well-informed. How could her little ragamuffin ever become a "man of God"? To her, regardless of his height (and now he towered over her), he was still a little boy -- wrestling with his brother in the backyard and teasing his sister.

The morning sunshine streamed through the window in Sue's room, surrounding the Reverend Schumacher's light brown hair with a halo-like glow. Sarah sat and stared at the miniature horses Sue had arranged on the windowsill, while the Reverend Schumacher considered all the possible meanings of the original Greek New Testament.

Sue had loved horses. She had nearly a hundred miniatures, and on her walls were dozens of pictures of horses, clipped from magazines. One picture, drawn by Uncle Harry, was a pen-and-ink sketch with a horse's skull large in the foreground, lying on a desert plain, and the Rocky Mountains and a herd of cattle in the distance. Sue had had it framed just before the boys went on their trip. Sue had been angry that she, who loved horses, wasn't being allowed to go on this amazing trip to Harry's wild west.

Today, Sarah surprised the Reverend -- it was she who had a passage she wanted to understand. "What does the word 'mansions' mean in the King James version of John 14:2, 'There are many mansions in my Father's house'? How can there be mansions in a house? A house is small. A mansion is big. It makes no sense. Why would one translator say 'rooms' and another 'mansions'? What did Christ really say?"

The Reverend Schumacher was delighted that Sarah had asked him. "Christ is speaking to his disciples at the Last Supper. He is telling them about life after death. He is reassuring them that there will be room enough for them in heaven, his Father's house. Perhaps it's meant as an echo of the Christmas story -- in heaven there will be room in the inn. But it suggests more than just space in which to live.

"The King James translation just anglicized the Latin, even though 'mansion' has a different meaning in English. The Latin is 'mansio, mansionis,' which means a stay or a sojourn, and, by extension, a halting place, a stage of a journey. Perhaps the passage means that life after death is a stage of a journey; that there are many such stages; that the journey through the house of God is a long one, requiring many rest stops. Perhaps our life here on Earth is just one such stage."

"And what are the words in the original Greek?" she inquired, expecting that the words of Christ would have magical power.

The Reverend quickly consulted the pocket-sized Greek New Testament he always carried with him. "En te oixia tou patros mou monai pollai eisin."

"And what part of that means many rooms or mansions?"

"Monai pollai."

"You mean like 'monopoly'?" she asked.

"That word has different roots, but the Lord works in mysterious ways. Far be it from me to discount the suggestiveness of our living language."

"And the key word is 'monai'?"

"Yes, in the singular, 'mone.' The letters are 'mu omicron nu eta.' It's pronounced like the impressionist painter 'Monet,' or like the French word for loose change -- 'monnaie.' It's an unusual word. It's meaning is very similar to the Latin 'mansio.' But, to the best of my knowledge, it has no derivatives in English. Money, monopoly, and monastery all come from different roots. You might say it's a word that died without offspring."

"I often think of my father's house," Sarah said as she stared up at Harry's drawing of a horse's skull. "It was one of those wood-frame houses connected to a barn with a passageway, so you wouldn't have to go out in the snow to get to your horse and buggy. It's still standing -- painted blue now instead of white, and they've turned part of the barn into a garage. We lived in the few steam-heated rooms in the center of the house. But in the summer, I spent lots of time in the many rooms of the attic, the barn, and the basement and in the 'secret passageway.' That was what we called the crawlspace under the peak of the roof that led from the barn to the house. I hope that God's house has rooms like that -- rooms to go off and be alone in, rooms where you can cuddle up with a good book, big empty rooms you can fill with your imagination.

"These last few nights I've dreamt that there's this secret room where I stored my most precious things -- things that have been lost for years: a rusty iron ring a boy gave me in grammar school, a notebook of poems I wrote, and photos of Sam my brother who ran away from home. And last night, it wasn't just the photos that were there, but Sam himself, and Sue, too. Sam and Sue had been playing a game of hide and seek. I just had to find the right room."

____________________________

Russ and Fred drove up Georgia Avenue, down Blair Road, and past all their friends' houses before parking the olive-green 1938 Nash two blocks from home. They were savoring their final hours of freedom and working out the last details of their grand entrance. They were bringing home a horse's skull -- the very one Uncle Harry had drawn -- as a present for Sue.

"What if she's over at Nancy's?" asked Fred.

"No chance," answered Russ. "Sue and her friends all sleep late on Saturdays."

"I'd better check those trenches she dug in the woods. That's where she goes on hot summer days like this, to curl up with a book."

"Wake up, Fred. How many times do we have to go over this? It's early in the morning. She's in the house. There's nowhere else she could be. Believe me."

"You're sounding like a preacher already."

"Okay, buddy," said Russ, slapping his brother on the back of the head and parrying a counter slap.

"What if Dad sees me first?"

"Dad probably took the truck. He's probably on his way to a building site by now. If not, he's doing paperwork in the study. Mom's the one to watch for. She'll probably be cleaning up in the kitchen, but she could be anywhere in the house. Your job is to find Sue without letting Mom see you."

"Okay. Okay. Enough is enough."

"Well, tell it all back to me so I know that you know it. What are you going to do once you find her?"

"I'll tell her our coming back early is a secret, that we're going to surprise Mom and Dad. I'll bring her out the side door by the driveway. And you'll be hiding in the bushes with the horse's skull."

"Brilliant. Now go to it, buster."

Fred slipped quietly in the back door of the house and crawled under the dining room table. From under the long white tablecloth, he could see and hear without being seen.

He heard his father's footsteps going from the kitchen to the study and then back from the study to the kitchen; pausing, then going back again and again. Fred had never known his father to pace like that. And where was his mother? She was the one he'd expect to be moving about. Normally, she was never still for a moment -- always cleaning and straightening, even while reading a book or talking to a friend. Something felt wrong.

Fred took a deep breath, waited until the footsteps returned to the study, then got up and tip-toed to the alcove by the fireplace. He could hear his father's heavy pacing even louder now.

Carefully, he leaned his head out of the alcove and looked around the living room. Something was missing.

The baby grand piano, the sofa bed, the two stuffed armchairs and the rocking chair were all in place, as before. But on the wall above the sofa, where once there had been a dozen small family photos, now there hung one large photo of Sue. He recognized the pose -- it was a formal professional shot, taken last Christmas. But this was an extremely large print -- nearly three feet by two feet. The matting and the frame were black.

Fred quietly walked over and knelt on the sofa to get a better look. Inside the glass, against the photo itself, were several newspaper clippings. They were death notices.

Fred heard his own scream before he realized that he was the one screaming, and then he couldn't stop screaming, running across the room, through the hall, tripping over his father, and bursting out the side door by the driveway, still screaming.

________________________________

Sarah was upstairs in Sue's room, with the Reverend Schumacher. She had heard footsteps in the driveway and once again had tensed, expecting Rem Jones, the mailman. Smiling and pretending to pay attention to the Reverend, she counted to herself. If there was another letter from the boys with no sign that they knew about Sue, she could expect her husband would once again roar with anger.

Instead, she heard a shrill unearthly scream, the sound of running and the side door slamming.

She and the Reverend raced down the stairs and bumped into Hank, who was getting back on his feet and moving toward the door.

Just then, they heard a second scream, almost as loud as the first, and a horse's skull loomed in the window, casting a dark shadow into the hall.

_______________________________

Frightened by Fred, Russ had let the skull fall on his own head. It stuck, blocking his vision; and when he tried to pull it off, the bone dug into his temples and ripped at his ears. He staggered around the driveway in pain, while Fred bellowed incoherently.

Meanwhile, Hank, Sarah, the Reverend Schumacher and Rem Jones watched in shock.

Later, Russ kept asking, "What were the odds?" He, who had never shown any particular interest in math, became absorbed in statistics and probability. He found some kind of comfort in calculating the odds of Sue dying, the odds that all twelve letters their mother had written would get lost, and then that he and Fred would decide to come home unexpectedly.

Every time he calculated the likelihood of three such unlikely events happening at the same time (even if his mother misremembered and it was only ten or even five letters she sent), the probability was one in a number so huge it was beyond comprehension -- many times greater than the number of atoms in the known universe.

When Russ told him about these calculations, the Reverend Schumacher said, "The ways of God are mysterious." Russ did not find that answer satisfying. His mind needed something to work on. He didn't want a pat conclusion. He wanted a direction to focus his energy on. If he had been told to say "Hail Mary" a million times, he would have done that. But being a Lutheran, he could find penance and hope of salvation only in working with numbers.

As a freshman at college that fall, Russ found it difficult to focus on his course work -- even the math course, which was introductory calculus, rather than the statistics he hungered for.

Meanwhile, at home, Fred took advantage of his parents' new attitude to him as the only child left in the house. He repainted the room he and Russ had shared and rearranged his furniture the way he wanted it. He ate what he wanted, stayed up as late as he wanted, and nobody hassled him about chores or homework. But after a few weeks of what felt like total freedom and self-indulgence, Fred felt restless and dissatisfied.

Before, Fred had always wanted to do things differently than his older brother, but had always buckled under to him when pressured. Now, there was no one for him to react to and define himself against.

One sleepless night, he moved to Sue's old bed and slept more soundly than ever before. Then he started visiting the Reverend Schumacher and spent a lot of time alone in the fields, staring at the sky and the horizon.

For years, he had been determined to go to a different college than Russ and pursue a different career. Now, to his surprise, he felt a growing bond of solidarity with his older brother. The following fall, he joined Russ at Gettysburg, intending, like him, to become a Lutheran minister.

___________________________

Pearl Harbor and America's precipitous entry into the war came near the end of Fred's first semester -- a time when Russ was close to failing several of his courses.

The war news stirred up memories of Uncle Harry's tales of the Great War and the aftermath in Paris and Constantinople and Cairo. Russ tried to join the Army, but couldn't pass the physical because of flat feet. Fred, who was miffed that his brother had taken that step alone, tried too, and was rejected because of a dislocated shoulder -- an old basketball injury.

Russ wrote to Uncle Harry about their problem, and Harry let them know that people were getting into the service who were in far worse shape than they were. He gave them advice on how to get around the bureaucracy.

Sarah and Hank had taken comfort in the knowledge that physical imperfection was likely to save their sons from the war. They were outraged at Uncle Harry's intervention.

Around the same time that Russ and Fred left for basic training, Sarah found out that she, at nearly 50, was five months pregnant. She had gone to her doctor several times, and he had insisted that the discomfort and weight gain she was experiencing were due to change of life. Now, having heard the baby's heartbeat, he embarrassedly changed his story.

Hank rejoiced -- it was a blessing from heaven. Sarah considered it an unaccountable burden.

During the last months of her pregnancy, she reread the Old Testament, lingering on the story of Sarah and Abraham and on the Book of Job. She also kept a journal, where she obsessively recorded everything she could remember about Sue, as if memory could resurrect her. On the fly-leaf of that diary she wrote: "Sue died while I was watching. All of a sudden, her body was there, but she wasn't. She -- whatever 'she' was -- left the body, passed from the room that was her body into another.

"I often dream of houses -- huge old houses with secret passages leading to hidden rooms.

"I don't believe in reincarnation. But I do believe there is something else, somewhere else, a hereafter.

"I live in my body. My body is a room I inhabit for a while. And then I pass to another room.

"It's as if Sue lived in a vast house, but she spent all her time in one little room, the size of a closet. And the door was shut. She didn't even know there was a door, until it opened, and she passed from one room to another."

When Charlie was born, he looked so much like Sue that it was painful for Sarah to look at him. Even though money was scarce, they hired a neighbor to help watch him for the first few years of his life.

Meanwhile, the private construction market dried up as the war made building materials scarce and drove up prices. Hank reluctantly gave up his independence and took a job as a foreman on a government project. Around that same time, he found out he had diabetes and had to carefully watch his diet, which added to his growing depression.

For two years, the only good news was the bored and boring letters they got from Russ and Fred, who were stuck at Army camps in the swamps of Georgia and Louisiana. Fortunately, they were never shipped overseas. When they came home on leave, they looked at little Charlie as an unwelcome intruder, to be ignored, at best.

Charlie learned to talk late -- no one was listening closely enough to his first attempts to recognize and reinforce the sounds that came close to "mama" and "dada."

By the time he was three, Charlie often tagged along with his father to building sites. He was tolerated as long as he didn't touch anything. He stood, patiently, and watched all day as they dug the foundations, poured the concrete and raised the framework.

Hank was both puzzled and pleased by this quiet, intense interest. Neither of his other sons had ever paid attention to his work. "I wonder what he day-dreams about when he's standing there like that," Hank told Sarah. "What kind of a mansion is he building in that mind of his?"

As soon as the war ended and gas rationing stopped, Hank drove Charlie around Washington, for the pleasure of seeing his wide-eyed reactions to all the sights.

Sarah mocked Hank, "You're old enough to be Charlie's grandfather. That's what you're doing, you know. You're not treating him like a son. You're just enjoying him like a grandson. Lord only knows where he's going to learn discipline and values, the way you spoil him."

That rebuke tickled Hank's fancy and encouraged him to take Charlie on more excursions, especially to the beach in the summer.

When Hank was a child, his grandfather had taken him to the beach at least once each summer. They'd go by train, from Lancaster to Philadelphia and Philadelphia to Ocean City, New Jersey.

Old Grandfather Arnold couldn't swim. The beach, for him, was a place for castles and dreams, and his were not ordinary sand castles. He was a craftsman, a cabinetmaker. He could make wooden pull-toys -- crocodiles and bears and elephants that opened their mouths and wiggled their ears and tails when you pulled them. And he made elaborate wood and sand castles on the beach.

All winter long, Grandfather made drawings based on pictures in books of castles in Ireland, Wales and Germany, where his ancestors had lived. He carved and warped pieces of wood until they were just the right size and shape, and prepared all the materials he would need to create those castles in exquisite detail, on the beach.

He didn't want to attract crowds. He'd look for a stretch of beach where there was no one around.

He didn't build them high on the beach, sheltered from the tide. He built them down close to the water, at low tide, and watched with glee when the sea came in and battered those magnificent towers and leveled them just as it did the crude little structures that three-year-olds made.

But that was the point of building on the beach -- to watch the waves come, to watch it all get swallowed up, time and time again. Grandfather and Hank would retrieve the wood when the waves started washing it away; and once again, they'd build -- the same castle or a new one -- at least one for each tide, for as long as they were at the beach.

As long as they had their dreams and their drawings, they could build a new one, as good as or better than all the ones that had gone before. And the sea was doing them a service by erasing them all. In washing the old ones away, the sea was preparing the surface for more castles, and more again.

Now Hank took Charlie to the beach and built sand castles for him near the family cottage on the Potomac. Hank had tried doing that just once before, for Russ when he was three; but Russ was so anxious about the outcome and so respectful of what his father had built that he took the fun out of it. Hank, like his grandfather before him, had built that first castle close enough to the water so nothing could save it. But Russ tried desperately to protect it from the tide. And when the waves won the battle, he sat and cried; and he never wanted to do it again.

Now, on the beach, Hank worked for hours, using all the bits of wood and cardboard he had carefully precut and shaped. Meanwhile, Charlie filled a bucket with sand and turned it over, and did that over and over again, until he had dozens of little towers all up and down the beach, and then ran and kicked them all down, with glee.

When Hank finally finished a huge castle with turrets, parapets, courtyards, and moats with drawbridges, he stood back, proudly, to show it to his son. At that moment, Charlie shouted, "Geronimo!" and belly-flopped right on top of his father's fortress, knocking it flat before the tide had a chance to get to it.

There Hank was -- a grown man building a sand castle, and little Charlie by knocking it down showed him in one stroke that he was really doing all this work because that's what he wanted to do -- not just to amuse his son. Hank got very mad at Charlie for that, but he loved him for it, too. Charlie got under his skin in a way the other boys never had. They made many such castles together.

Chapter Three -- Aunt Rachel and the Wizard of Oz

In July of 1946, Russ, recently discharged from the Army in Georgia, arrived home with his new bride, 17-year-old Rachel. He had the cab stop at the corner, and left the luggage there under bush.

Russ paused to admire Rachel. When she was disoriented, as she was now, she looked very young, naive and vulnerable. But alone with him, she had the capacity to turn bold and provocative. He enjoyed comforting her, then shocking her, to watch her switch from one extreme to the other. He was fascinated by this fluctuating, lustful innocence of hers.

He took hold of Rachel's hand and pulled her along, as he slid quickly and quietly toward the house. They stayed behind hedges, ducked behind an oak tree, then dashed to the front door.

"Remember," he told her, "they don't even know you exist. Stay right here. I'll go around the side. It should take five to ten minutes for me to set them up. Then I'll get Mom to open the front door, and you'll say ..."

"Hello, Mom, I'm your new daughter."

"Right. You've got it. The scene will be unforgettable. Just stay put and wait for your cue."

Russ crept back the way he had come, and picked up the suitcases at the corner. Then he strolled casually up the driveway to the side door. He tried to maintain a poker face, but, inside, he was shaking with laughter at this surprise he had prepared for his parents.

He knew they would love Rachel. They would be as delighted as he was that he had been so lucky to meet her and win her. It was as if he had won a million dollars and wanted to spring the news on them with dramatic flare.

And he had another surprise in store for Rachel. He had never told her he had a baby brother. The way she loved kids, she would go wild over little Charlie.

"Mom! Dad! I'm home!" he hollered as he opened the door.

No answer.

"Mom! Dad!" He put the suitcases down and ran to the living room. It was empty.

He hollered even louder, "Mom! Dad!" and rushed into the hall and up the stairs. Still no answer.

He ran back down again, and, winded and disappointed, opened the front door for Rachel.

"Hello, Mom... " she blurted out, then broke into laughter.

"Hush," Russ put a hand over her mouth. "They aren't here. They must be visiting a neighbor. We'll surprise them yet. Come on in. I'll show you around. Then I'll go hunt them down and set them up. Believe me, this is going to work out great. I can't wait to see the look on their faces."

"God!" she exclaimed as she walked in the door.

"Watch your language. How many times do I have to tell you -- my parents are touchy about things like that. Never, and I mean never, use the name of God in vain in this house."

"All right, already. But this place is wild. It's just the way you described it." She went straight to the fireplace and curled up on the bench. "Come on over here," she hiked up her skirt above her garter belt and started unbuttoning her blouse. "You know how I've been looking forward to this."

"Not now. They could walk in the door at any moment."

"But we're married," she coaxed. "Remember, anything goes when you're married."

"But not in my parents' house. Besides, there will be time enough for that later."

"Russ, you are simply unbelievable. But I love you anyway." She rushed to him and nuzzled her head into his shoulder. When she stood straight, her forehead was even with his chin.

He slowly ran his hand through her long, straight black hair, and caressed her ears with the large gold-plate loop earrings he had given her. He held her close. "Okay, you little Delilah. We both know you can get your way with me whenever you want. But please don't tempt me now. Come on, I want to show you the house."

He led her upstairs, then had her wait in the hall while he scampered up a pull-down staircase to the attic, and came back with the horse's skull.

"You mean that really happened?" Rachel asked. "That whole wild episode?"

"Of course. And come in here. This was Sue's room. There's the drawing Uncle Harry did of the skull. See, it's a good likeness." He put the skull on the floor in front of the picture. "And over there," he pointed to the other wall, "is that blow-up photo of Sue that spooked Fred when he saw it in the living room."

"God," she started to say, then stopped herself. "Gosh, this room looks like a young girl still lives in it."

"Mom's left everything the same, like she expects Sue to come back some day. From what Dad says in his letters, Mom's gotten superstitious. Every year, on Sue's birthday, she bakes a cake, and sets it up with the right number of candles, as if Sue were still alive and getting a year older each year. According to Dad, Mom claims she has seen the shadow of a young girl a couple times, in this very room, by that very window."

"Oh, I'm so scared of ghosts," Rachel murmured, nuzzling up to him again. "I need a big strong man to protect me." She turned her head to the side so their lips could touch.

He laughed and pushed her back, "Not now."

"But we've never kissed in a haunted house before."

"And you know I couldn't stop with just kissing you. Wait here. I'll go find my parents and bring them back. Then I'll come up and tell you my new plan."

"Why not just tell me now."

"Believe me, if I knew it, I'd tell you. I'll have to figure it out as I go along."

He threw her a kiss from the door.

___________________________________

When Russ first came barging into the house, little Charlie, age four, was playing with tin soldiers in his parents' room. Frightened by the shouting and the loud steps, he crawled under the bed and hid. Then he heard soft voices coming from Sue's room. Then loud footsteps rushed downstairs again.

Slowly, cautiously, Charlie crept out and inched his way toward Sue's room.

Now, standing in the doorway, he saw Sue herself, sitting in her old room, with light streaming through the window behind her. Her face was in shadow, but even from the doorway he could feel the warmth of her love, a warmth he had never felt before.

She was playing with her miniature horses on the windowsill. He'd never seen a grownup play make-believe before. Her hands slid from one figure to the other as her attention moved. Then she tossed her head back and shook her hair as if she, too, were a horse.

He walked up to her, slowly, without saying a word. He knew without a doubt who she was and presumed that she knew him -- after all, he was her brother. Even a ghost would have to know that much.

He was not so much surprised to see her as surprised that it had taken her so long to appear to him.

Charlie tripped over the horse's skull on the floor. The girl turned toward Charlie. Sue had disappeared, and in her place stood another girl, about the same age -- a pretty girl, with long black hair. Charlie screamed an unworldly scream, and the girl ran up to him, picked him up and hugged him tight to comfort him.

"Where did she go?" asked Charlie in confusion. "What did you do with her? Where did you hide her?"

"Who?" asked Rachel.

"Sue. My sister. She was just here. You made her go away. Tell her you won't hurt her. Please call her back."

___________________________________

Meanwhile, Sarah, walking back to the house from the end of the driveway, saw the shadow of a young girl at Sue's window. She stopped, shut her eyes, turned away, then looked again, and the shadow was still there. She took her glasses out of her pocketbook, wiped them clean on her blouse, and looked again. The shadow was still there.

With trembling voice, she began to repeat the Lord's Prayer, "Our Father..."

Then the shadow moved and an unworldly scream broke loose -- Charlie's scream.

Sarah ran up the driveway, stubbed her toe on the doorstep, banged her knee on the screen door, tripped up the stairs and found this strange girl with a wild frightened look in her eyes, holding little Charlie.

The girl hesitated in confusion, then blurted out, "Hello, Mom, I'm your new daughter."

Sarah grabbed a broom from the corner and waved it at her, shouting wildly, "Out, you madwoman, you imposter, you demon."

Rachel instinctively clutched Charlie and ran through the upstairs hall, down the stairs, and out the side door to the driveway.

Sarah came racing after her, waving her broom, and shouting, "Un-hand my son, you, you..."

Rachel cowered, helpless, with her back to the wall. "Your son?" she asked. "But your sons are in the Army, or were in the Army. You're ..."

"Old enough to be his grandmother? Yes, indeed, but he's mine." She reached out her arms to him. He hesitated a moment, then pulled away from Rachel and ran to his mother. She picked him up and hugged him more warmly than ever before. Then she shifted her attention back to the intruder. "And who are you to be playing Goldilocks, wandering into other people's homes?"

"As I tried to explain ..."

"Don't explain anything. Just tell me who you are!"

Rachel hesitated, then answered, "My name is Mrs. Arnold."

"What?"

"Mrs. Rachel Arnold. Mrs. Russell P. Arnold. Your son's new wife."

"Impossible. You're just a girl, no older than..."

"Than your daughter Sue would have been? Russ told me about her many times."

Stunned, Sarah simply stared and held Charlie even tighter.

"Russ wanted to surprise you. I thought we should invite the whole family to the wedding, or wait and have the wedding here, or at least tell you what we were doing. But Russ insisted. He's a big kid the way he loves surprises, and I love him for it. He had this whole script he had worked up -- what he was going to say to you and Mr. Arnold, and how he'd get you to open the front door and there I'd be standing. But nobody was home when we got here. Nobody except the little one."

"Charlie."

"Yes, Charlie. That must have been another of Russ's surprises -- not telling me he had a little brother. That rascal. If I didn't love him so much, I'd hate him," Rachel laughed.

Sarah stepped forward to take a closer look at this girl. Confused and innocent, wearing a plaid skirt and white blouse with saddle shoes and green socks, Rachel looked like a ninth grader just home from school.

Russ emerged from the backyard, walking with his father. "Oh," he stopped short. "I guess you've met already."

"This little girl says she's your wife."

"She most certainly is." He ran up and lifted Rachel, with an arm under her knees and another under her back.

"Is this some sort of joke?" asked Sarah. "She's not old enough to be married."

"She's 17, Mom. In Georgia, that's nearly an old maid. Besides, you were just 16 yourself when you married Dad."

Rachel craned her neck upwards toward Russ, perhaps to kiss him or perhaps to bite him, in anger at the humiliation he was making her go through.

"Seventeen?" repeated Sarah. "Why, Judy Garland..."

"What, Mom?" asked Russ.

"Judy Garland was seventeen when she played Dorothy in the Wizard of Oz. Who could ever imagine Dorothy as a married woman?"

"Oh, that's a wonderful movie!" Rachel nuzzled her head at Russ's neck, all sweetness now. She kissed him behind the ear. "I saw in the paper that it's playing again. When it first came out, I saw it three times and loved it more each time I saw it."

Sarah stared at her, unaccustomed to seeing such open signs of affection. She held Charlie tighter. She was still trying to absorb the shock that Russ was married. "Sue was ten when I took her to it. I haven't been to another movie since. Come to think of it," she added distractedly, "Charlie has never been to a movie at all."

"Oh, but he must go. He simply must," insisted Rachel. "Why that's the most magical movie of all, and movies are the most magical experience on earth. Please let me take him, Mrs. Arnold, please."

Sarah turned now to Russ, now to Hank. She had no idea what to do or say, and she could tell that Russ and Hank were equally confused. Her son had married a puzzling and perhaps wicked little girl. That was an incredible mistake that could throw all of their lives in disorder. But the question at hand was whether to take Charlie to the movies. Sarah felt dizzy. On impulse, she responded, "We'll both take him."

"Great idea," Russ confirmed, with a sigh of relief. "I'll check the times in the paper. That'll give you two a chance to get acquainted while Dad and I catch up and take care of the yard."

"The lawn could certainly use a mowing," added Hank, with a smile.

Sarah smiled too, put Charlie down, and gave him a pat on the behind. "Run on upstairs now, wash up, and put on your best Sunday clothes. And don't forget to wash behind your ears and under your nails. Let's make an occasion of this -- it's not every day you see your very first movie."

_______________________________

Charlie was confused, but he did what he was told. It was bad enough having to get dressed up to go to "God's house" every Sunday. Now he had to get dressed up on Saturday too, to go to some new kind of place. Rachel said that there would be lots of people. And Mom said he'd have to behave and stay still and keep quiet. He hoped this wasn't something he'd have to do again and again, like going to church. He'd rather stay home with Dad and Russ and play and work in the yard. But he knew there was no arguing with Mom.

The building was as big as a church, but instead of wooden benches, there were grownup seats with arm rests. Mom wanted to sit in the back and Rachel up front; so they sat in the back. Then Charlie stood on his seat to see over people, and Mom picked him up, and they all went to the front row.

He was just getting comfortable in his big soft seat when the lights went out. It was darker than nighttime. No light at all. With one hand he grabbed his mother's arm, and with the other he found Rachel's hand. He held his breath and squeezed tight.

Then the curtain opened, and he was almost knocked over with the light and the music. Creatures appeared that were many times bigger than anything he had ever seen before. He wanted to ask, "Which one is God?" But he figured he was supposed to know without asking, and Mom might get upset that he hadn't paid attention in Sunday School.

Rachel gave him a hug, and whispered to him, "They look alive, but it's just a trick. Look up. See that beam of light. That's where they come from. They're just light on a screen. It's nothing to be afraid of."

"Oh, I'm not afraid," he answered, then quickly looked over at Mom to see if she was mad at him and Rachel for talking. But she was just staring at the screen and smiling.

Cartoons switched to news reels, to previews, to a Tarzan serial, to the feature. But to Charlie, it was all one long sequence of pictures -- one surprise after another -- everyday-looking people and things mixed together with storybook things, like in a dream.

Rachel leaned over and whispered. "I used to live in Kansas. But I never saw a tornado," she added.

"What's a tornado?"

"That is," she said, pointing to the screen, where wind was blowing things every which way.

When the picture switched from black and white to full color, Charlie jumped like he had when light first hit the screen.

Afterwards he remembered Rachel's words more clearly than the words of the movie. And the pictures he remembered best were the ones he saw when she spoke. Years later, he would say that her voice had controlled a camera shutter in his mind. "Ruby shoes ... Munchkins... Scarecrow... Tin Woodman... Lion..." -- one snapshot after the other, held forever in memory.

When the Great Oz first spoke, Charlie leaned over close to Rachel and whispered, "Is he God?" But she didn't answer.

The cackling laugh of the Wicked Witch of the West cut right into him. She scared him so hard it hurt. He shut his eyes and tried to think of other things.

He slept through the rest, his scary dreams mixing with sounds and pictures from the movie.

He was glad when it was over and they were safely out on the sidewalk again.

Then Rachel started singing the song about rainbows and Mom joined in. And Rachel took his one hand and Mom the other, and they started dancing and skipping up the street, chanting, "Lions, and tigers, and bears! Oh, my!" It was like they were kids with him or he was a grownup with them. He laughed like he'd never laughed before, and hugged them both with abandon. And they hugged back like he were the most important person in the world and they both wanted him all to themselves.

________________________________

That day, and every day for a week, Charlie kept talking about the movie and asking questions. Rachel read him the book. Then they went to see it again the next Saturday, and the Saturday after. Gradually, he began to see the story, instead of just pieces. He was fascinated with it, and he loved the grownup attention he got when he talked about it.

"Is our house like that, Mom?" Charlie asked at bedtime. "Can it take us to some other world?"

"Charlie, don't be silly. You know that's just a story, like a dream."

"You mean dreams aren't real?"

"I suppose they're real in their own way. But things aren't just what they seem in dreams. One thing stands for another."

He didn't know what that meant. But he kept asking, "Do you dream, Mom?"

"Of course," she answered. "We all do. That's part of being human -- like remembering and building things and talking and reading."

"What do you dream, Mom?"

"Lots of times I dream of houses," she admitted.

"Ones that fly and fall on wicked witches?" he asked.

"No, I dream of this house and the house I grew up in. Sometimes the house has extra rooms -- attics on top of attics, and passageways leading to new passageways. Some are empty, and some are storage areas, like at our summer house, with trunks and boxes stacked high. I go wandering through those rooms, from one to another, opening boxes looking for a lost recipe as if the world depended on my finding it. Or I walk into a room that's furnished like a living room, well kept and dusted, with a warm cup of tea sitting on the table, waiting for the owner, whoever she may be, to come back. Or I wake up in a strange bed in one of those rooms, and can't find the passage that will get me out again. Sometimes I think I catch a glimpse of your sister Sue, playing hide-and-seek in those rooms."

"Have you ever seen me there?" he asked.

"No, I haven't seen you in my dreams, and not Rachel -- not yet. But I will some day. I'm sure of it. That's the way dreams are."

After that, Charlie made a habit of asking his mother about her dreams when he went to bed at night. Even when she was busy and in a hurry, she would linger a few minutes to talk of that. And his own dreams, instead of jumping from here to there to everywhere, like they had before, began taking shape from pieces she told him -- often taking place in huge old houses with unexplored rooms. He was no longer afraid of falling asleep.

Chapter Four -- Charlie's Coming of Age

Sarah Brehm was born in 1892 in Plymouth, New Hampshire, a small town where Daniel Webster had lost his first court case, in a one-room schoolhouse that was now the town library. Nathaniel Hawthorne had died there, too, at the Pemigiwasett House -- a large white frame hotel, just a block from the Brehm house.

The Brehms had a typical Victorian family -- many children and few survivors. Sarah was the youngest. Sam, the sibling closest to her in age, ran away at 12. They heard he got to Boston and took ship, but no one had seen him since. Her sister Margaret became hysterical in her late teens and was put away in an insane asylum, where she died 10 years later. Another brother died of pneumonia. Two others died as infants. Sarah's one remaining sibling -- George -- volunteered for World War I, and, after the war, settled in New York City, from which he occasionally and unpredictably appeared, bearing gifts.

When Sarah was six, her father and his brother-in-law Harry headed west to see if the prospects there were as good as newspapers and magazines claimed. They spent a year wandering and doing odd jobs on farms in Kansas and Oklahoma.

Harry stayed and had his wife come West to him. But Sarah's father gave up and returned East to his family, to spend the rest of his days working in a shoe factory in Plymouth.

Sarah had met Hank Arnold, her husband-to-be, at the Pemigiwasset House. She was doing maid's work there during summer vacation from high school, and he had come north for the mountain air, on his doctor's recommendation. In late August and September, he suffered badly from hay fever, everywhere but in the mountains.

Aside from his allergies, Hank was muscular and tough -- a successful builder who had begun as a construction hand. He was the only son of a Pennsylvania farmer and grandson of a cabinetmaker. Hank wasn't interested in farming. From the day when his grandfather first showed him how to make sand castles using boards for support, Hank had dreamt of building houses -- one after the other -- whole neighborhoods of houses, teeming with children. After finishing high school, he hiked to Washington, where he found work in the flourishing building trade.

When Hank and Sarah married, he was 21 and she 16. He built a house for them in Silver Spring, Maryland, near Washington, D.C. He also built a summer cottage at Colonial Beach on the Potomac in Virginia.

The cottage was near a lighthouse, across the street from a grove, just above the river bank. The ground sloped upward. In the front, the main part of the building (six bedrooms and the front porch) was on stilts, so it would be protected from high water in case of hurricane. In the back, the dining room and kitchen were at ground level. Under the bedrooms was a storage area, with lattice sides and a dirt floor. Above the bedrooms, accessible with a pull-down ladder, was an attic which could sleep four people in beds and up to a dozen on the floor. In the back, there was a grape arbor, a garage and an outhouse. To the side were a stone-and-masonry goldfish pond and a yard large enough for volley ball, badmiton, and croquet.

When Sarah's Uncle Harry returned from World War I, he stayed at the cottage for an entire summer before heading west. He had volunteered to stay overseas two years after the end of the war, and had just heard from his first wife that she was divorcing him. Day after day, he puttered aimlessly along the beach, heaving stones and shells at unseen targets. Then in the fall, he headed West to start a new life. He left behind several trunks full of military paraphernalia and souvenirs from Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. Those trunks gave the summer house an aura of the exotic.

______________________________________

After taking Charlie to The Wizard of Oz for three Saturdays in a row, Rachel wanted to take him to the cottage, which she had heard about from Russ. Sarah insisted on going too; so Hank took them all.

As soon as the car stopped, Charlie ran out with his bucket and started making quick sand castles along the waterline. Hank followed, making more, then Rachel, then Sarah. Then they all cheered as Charlie ran up the line, stamping on each and every one of them.

Russ watched from a distance. To him, Charlie was still a baby. This four-year-old was a total stranger he didn't know how to relate to. And it was hard to believe that was his fifty-year-old mother, up to her ankles in wet sand, splashing like a ten-year-old.

Not to be outdone, Russ scavenged in the storage area for Uncle Harry's World War I army gear. Then he crept across the street, and hid behind tall grass near the main path. There he set his trap.

When Charlie and Rachel came strolling back up the path, Russ pulled a string, which lowered the grass, revealing what looked like a couple of soldiers, dug in, with guns at the ready. Then he set off firecrackers.

Rachel burst out laughing. But Charlie froze in terror, until Sarah picked him up and raced back to the house to calm him.

"How could you?" muttered Hank in disgust.

The next day, Russ sat on the porch and watched in amazement as, once again, his wife and parents played on the beach like kids. He wanted to join in the fun, but didn't know how except with practical jokes. This time he rigged the house with water balloons. Charlie, who was the first one back, was the perfect victim. Running in through the kitchen door, he was hit by the first, then tripped in confusion and triggered a second and a third. Rachel thought it was hilarious, and this time Charlie laughed too.

After that, Charlie wanted Russ to teach him tricks and surprises that he could play -- like short-sheeting beds and putting grapes in slippers. And on cloudy, cool days, the two of them would get out the old army gear and dig foxholes on the beach and in the grove, and play war games with the neighbor kids.

Sarah remembered that summer as the time when she learned to enjoy her son Charlie. She was always grateful to Rachel and Russ for that. But at the same time she felt guilty for feeling so happy, and feared she would never be able to establish the same distance and same level of discipline as she had with her other sons. She was afraid of what might become of him with such an unorthodox upbringing, but she couldn't help but roll in the sand and the waves with him, now that Rachel had shown her what fun it could be.

__________________________________________

That fall, Fred got out of the Army and returned to Gettysburg College. He became a Lutheran minister and moved to Illinois, where he married Francine and had two sons -- Jimmy and Georgie.

Russ finished college at the University of Maryland, became an actuary for an insurance company, and moved to nearby Rockville, Maryland, where he and Rachel had two sons -- Frank and Eddie.

The beach house was where the cousins of the new generation met and played with one another and with their Uncle Charlie.

Charlie didn't really belong in the generation of his brothers or the generation of their children. He was 20 years younger than his brother Russ, and eight years older than Frank, to whom he was more like a big brother than an uncle.

This is where the extended family would gather -- some of them for the whole summer, some for weekends, and some just for the Fourth of July. There were plenty of rooms. And when friends and more distant relatives showed up, as they often did, there was always room to spread out more sleeping bags.

This was where Hank got used to being called "Grandpa" and Sarah "Grandma," even by their own sons and daughters-in-law -- even by Charlie. It was also where they could still sometimes act like kids themselves, joining Charlie and their grandchildren and their daughter-in-law Rachel to build and break sand castles.

And this was where Charlie could get away with every devilishness he could think up. He was now the practical joker, terrorizing and delighting the young kids. Russ, who no longer indulged in such childishness himself, laughed at and encouraged Charlie's booby-traps and pranks, and prodded his own son Frank to join in.

Charlie also developed an endearing manner with the older generation. When he went too far in his horseplay and was at risk for serious punishment, he could put on a sincere apologetic manner and admit his fault -- "everybody makes mistakes" -- and nothing came of it.

Once, when Frank was seven and Eddie two, Rachel asked Charlie to babysit.

Russ objected "Charlie at the beach is one thing. But in this house with these kids -- that's something else. No way. Absolutely no way."

But the regular babysitter had taken sick, and Rachel was determined to go to this party. There was no choice but Charlie.

"Now look, kid," Russ told him. "To be on the level with you, I think you're too immature for this. Yes, you're 13 years old. Yes, you're tall for your age; but from what I've seen of you over the summer, you're more of a kid than Frankie is. Today I want you to act older than your years, not younger. Surprise me. Show me you can act like an adult."

Charlie smiled broadly -- too broadly, Russ would recall -- and assured him. "I can act like an adult. Just trust me."

From what Russ and Rachel could determine afterwards, Charlie did indeed fulfill his promise, after a fashion. When they got home, their neighbor Mr. Callahan was waiting on their doorstep; and the house was filled with cigarette butts and empty beer cans.

Apparently, Frankie had woken up, heard laughter and talking in the living room, and peaked around the corner. He saw Charlie with a bunch of older boys -- "grown men," he insisted, but they were probably about 18. They were drinking beer and swapping jokes. Frankie didn't understand what they were saying and fell asleep in the hall. When he woke up, the house was dark and quiet.

"Charlie!" he called.

No answer.

"Mommy! Daddy!"

No answer.

Eddie woke up screaming. Frankie panicked and screamed too.

Mr. Callahan found Frankie on the sidewalk bawling, "Mommy! Daddy! Where are you?" Mr. Callahan fetched Eddie, too, and brought them both to his house, and left a note on the door.

Charlie came over when he got back. "I thought Frank was asleep," he explained. "I just went out with my friends to get more beer." That explanation from a thirteen-year-old did not go over well with the neighbors.

Russ was furious at the time. But after a few years and many retellings of the tale, even Russ couldn't help but laugh at how Charlie did indeed "act like an adult."

___________________________________

Rachel maintained a special friendship with Charlie. When the family got together, she'd bring him presents, and always had something she wanted to talk to him about -- a new movie or book. And Charlie would ask her about her dreams, and record them in a notebook.

Thanks in part to this practice with Rachel, Charlie developed a remarkable ability for getting along with adults. At fifteen, when he was taller than his father, and even a little taller than his brother Russ, Charlie played master of ceremonies at family gatherings -- first as a joke, and then as his expected and natural role.

He enjoyed being the center of attention and being in control.

At parties he found just the right words to help strangers mix. At school dances, he made a habit of dancing with all the wallflowers. He was at ease with all girls -- bright and dull, beautiful and homely.

By the time he was 18, Charlie was confident enough to practice his powers of flirtation on any woman, regardless of her age. He would give that woman his full interest and attention, keeping her off-balance and animating her, while keeping a respectful distance. This tension of desire and restraint was exciting and liberating -- particularly to married women twice his age.

___________________________________

At Colonial Beach, Rachel luxuriated in Charlie's attention. Russ was inclined to get wrapped up in his work and his numbers, and, for weeks at a time, would seem to forget that she was a woman, regardless of her efforts to remind him. At the beach, the attention of this virile and handsome teenage brother-in-law made Rachel feel young again. She wore a revealing two-piece bathing suit that would have scandalized Russ, had he noticed.

She was proud of the figure she had maintained after having two babies. Yes, there were varicose veins on her legs, but a summer tan soon masked those. Strangers found it hard to believe that her oldest son was as old as he was.

On Saturday of Memorial Day weekend in 1960, when Charlie was a high-school senior, Rachel found herself alone with him at the cottage. Everyone else was downtown at a carnival and would be gone for hours.

Rachel could feel the silence in the house as she stood half-naked in her room -- the heavy silence, punctuated by footsteps that could only be his, walking toward her door, hesitating, then continuing down the hall, out the door and down the front stairs. She didn't know what she would have said or done if he had knocked or even opened the door.

She felt ashamed of herself for having such thoughts. But yet it gave her pleasure to think that she was that attractive, that he should actually want her physically and have to hold himself back.

She pushed the top and bottom of her bathing suit a bit lower, before she grabbed a towel and ran after him toward the beach.

Charlie was leaning against a pine tree in the middle of the grove. Out of the corner of her eye, she could feel his eyes following her, and she walked with more than her usual sway.

She pretended not to see him and called, "Charlie! Where are you, Charlie? Charlie, did you go off to that carnival and not say a word?"

When he didn't answer, Rachel felt like a mischievous teenage girl. She stretched out her blanket in a sheltered area below the bank, where she couldn't be seen from the road, or from any of the other beaches up and down the river, and just a few feet out of the range of Charlie's view. There she boldly undid the top of her bathing suit and stretched out on her belly to sunbathe.

She heard him take a few steps closer on the bank. She pretended to shut her eyes, but through her eyelashes saw him duck and lie down, hiding behind a bush just ten feet away and gawking at her. She felt deliciously evil. She hadn't felt so desirable and desired since Russ first undressed her fourteen years before.

She sensed he was about to back away, but she wanted this sensuous tension to continue. Smoothly and gracefully, she rolled over, exposing her breasts.

She even dared to look him straight in the eye, very quickly, so he knew she knew, then looked away, not to embarrass him or force him to speak or to leave. She leaned back on her elbows, thrusting her breasts up and forward to grant him a full view.

Rachel and Charlie lay like that, silently for nearly an hour. From time to time, Rachel would change position for comfort, but still give him a picture-postcard view.

Then, still looking away, she stood up, put on the top of the bathing suit and walked back to the cottage as if nothing had happened.

That night, when Russ and Rachel were going to bed, Rachel asked, "What is the probability of a woman becoming pregnant from making love just once without a condom?" As he looked up, she slowly, like a stripper removed her bathing suit, revealing her now suntanned breasts. Her feelings of guilt from her outlandish behavior that morning, added zest to the passion which drew her and Russ together, like a pair of teenagers alone at last after months of groping and lusting. Nine months later, nearly eight years after the birth of Eddie, she gave birth to their third son, Johnny.

______________________________________

That same night, after everyone was in bed, Charlie went out to the beach alone. There, by the light of the full moon, he built a huge and elaborate wood-and-sand castle -- using bits of lumber from the storage area under the cottage.

Just after dawn, Hank, on his usual morning walk, found him there. "That's a fine castle, son," he remarked. "I've never seen you do anything like it before. Have you been sneaking down here in the dark to practice?" he chuckled.

"No, this is the first. And it will be the last for a while, too."

"But we have a long summer ahead of us. We could work together on something like that. I'd very much like to, if you'd let me."

"Maybe some other time, some other place," he stared down at his feet. He had come to the beach to be alone with his thoughts. This encounter was unexpected, but Charlie was relieved to have this chance to talk to his father in private. "Dad," he continued.

Hank smiled. "Yes, son."

"I'm joining the Army."

"Well, that's certainly a choice to consider, but I thought you had your heart set on college in the fall," Hank responded in a friendly, but patronizing tone. "Let's talk about the army in a few weeks, after you've graduated from high school. Then we can weigh all the pros and cons together."

"No, Dad. I've made up my mind. I'm not going back to school. I'm not going to take finals. I'm not going to graduate. I'm simply going to join up. Please don't try to talk me out of it," he quickly added. "It was a difficult decision. Please don't make it any more difficult."

"But why are you doing this, Charlie? What's your dream?"

"I've got lots of them, Dad. Maybe that's the trouble -- there are so many dreams floating around in my head that I don't know which one is really mine. Maybe I'll become a builder like you, or a soldier like Uncle Harry, or a minister like Fred. Or maybe I'll write books or make movies. I can see myself doing any of those things. But mostly, I see myself with women -- almost every woman you can imagine. And that just makes everything confused. I need to get away and sort it out before I make a total mess of things."

"Well, Charlie, I hope you do sort things out. Most folks never do." Hank shut his lips tight. He looked long and hard at the sand castle, then simply sat on it, making himself comfortable, as he knocked over towers and walls. Charlie laughed and sat beside him -- it was a very big castle.

"You know, I don't talk much," said Hank. "Your mother's the one for words. But this sand castle of yours has got me to thinking. What I mean to say is -- I like to think that what matters is what you do, more than what you say. I like to think that what I do with my hands is what makes me who I am. I like to be in control. But time and again, I see dreams and stories and ideas making more of a difference than just plain facts. I can't make sense of it, but it happens even to me. Why am I a builder?" he asked Charlie.

"I suppose because you wanted to be one."